Seabed mining is emerging as a hot topic in resource extraction, promising a treasure trove of minerals essential for modern technology. But before we dive headfirst into the depths of the ocean, let’s explore what seabed mining entails, its potential benefits, and the environmental concerns that come with it.

What Is Seabed Mining?

Seabed mining refers to the process of extracting minerals and metals from the ocean floor. This practice targets deposits that have formed over millions of years, such as polymetallic nodules, seafloor massive sulphides, and cobalt-rich crusts. Minerals like nickel, cobalt, atc are found in these deposits and are essential for the production of batteries, electric cars, and other green technology.

Types of Seabed Resources

- Polymetallic Nodules: Found on abyssal plains, these potato-sized nodules contain a mix of metals, including manganese, nickel, copper, and cobalt. These nodules, which are thought to contain billions of metric tons, are most prevalent in the Pacific Ocean’s Clarion-Clipperton Zone.

- Seafloor Massive Sulphides: Located near hydrothermal vents, these deposits are rich in metals like copper, gold, and silver. They form in unique ecosystems that thrive in extreme conditions.

- Cobalt-Rich Crusts: These crusts develop on underwater mountains and contain various metals, including nickel and lithium. They are formed slowly over time and are often found in shallower waters.

The Economic Potential of Seabed Mining

The seabed is believed to hold vast reserves of minerals, with estimates suggesting a potential value of up to $20 trillion. This economic opportunity is particularly appealing as land-based mining faces challenges such as declining ore grades and stricter environmental regulations. Companies are eager to tap into these underwater resources to secure a stable supply of critical materials for the energy transition.

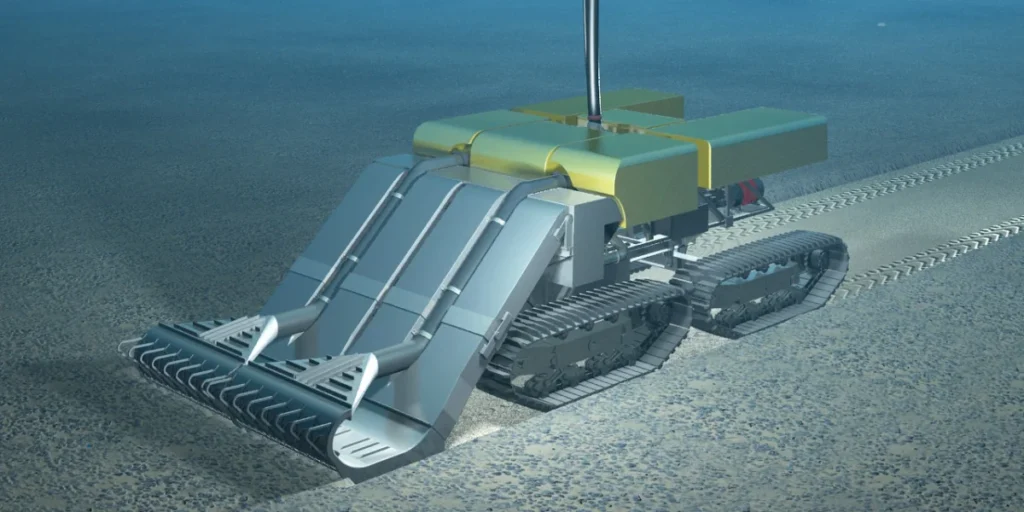

Technological Innovations

Recent technological advancements have made seabed mining more feasible. Innovations such as remotely operated vehicles and autonomous underwater vehicles are being developed for the purpose of exploring and extracting resources from the ocean floor. These machines can operate at extreme depths, navigating complex underwater terrains while minimising environmental disruption.

Environmental Risks and Scientific Gaps

Deep-sea resource extraction creates significant environmental challenges. Scientists still work to understand these issues fully. Research shows that seabed mining could damage marine ecosystems in multiple ways. The effects go way beyond the reach and influence of the mining sites.

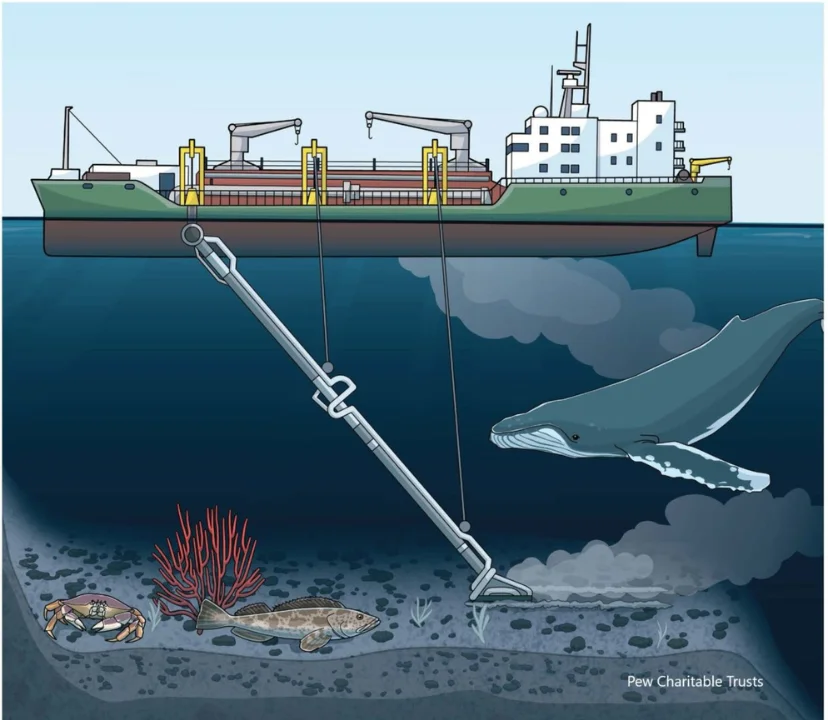

Sediment Plumes and Midwater Ecosystem Effects

Seabed mining’s biggest problem involves sediment plumes – clouds of disturbed particles that spread through the water. A single nodule-mining operation could create 30,000–80,000 m³ of sediment daily. This amount would fill 4,000–10,000 dump trucks. These plumes form when mining vehicles rake the seabed or mining ships discharge unwanted material after separating ore.

Models suggest these plumes could spread over tens of thousands of square kilometres way beyond mining sites. Recent studies show 92-98% of sediment settles within 2 metres of the seafloor. The remaining particles can drift far distances. Cold-water corals and phyltire-feeding organisms face real risks. Higher levels of suspended sediments make it harder for them to feed and breathe.

Long-Term Habitat Disruption and Recovery Delays

Experimental mining sites reveal troubling long-term effects on seafloor ecosystems. Scientists found that damage tracks from mining vehicles conducted in 1989 remained visible even 40 years later. These disturbed areas still lack microorganisms vital to ecosystem function.

Recovery takes an incredibly long time. Scientists estimate hundreds of thousands of years for the sediment layer to rebuild. Nodules need millions of years to regrow. Mining creates permanent habitat loss. Polymetallic nodules serve as vital attachment points for many deep-sea organisms.

Unknown Effects on Microbial and Pelagic Life

The unknown aspects of deep-sea ecosystems raise serious concerns. Scientists estimate up to 92% of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone’s benthic species are new to science. Millions of undiscovered species might live in the deep ocean. This lack of knowledge makes it sort of hard to get one’s arms around mining’s full effect.

Microbial communities play vital yet understudied roles in deep-sea environments. These tiny organisms help with carbon sequestration and methane regulation, and they are the foundations of deep-sea food webs. Mining disruption could release stored carbon from seabed sediments, which might affect ocean chemistry and climate regulation.

Noise from mining activities presents another unexplored risk. Research shows noise from a single mine travels about 500 kilometres through water. This could disrupt marine mammals’ communication and navigation patterns.

Underwater Cultural Heritage at Risk

The seabed remains 80% unmapped. Deep-sea mining threatens both known and undiscovered underwater cultural heritage (UCH). These sites include prominent shipwrecks, artefacts, and areas important to Indigenous communities.

International Seabed Authority draught regulations don’t protect cultural heritage enough. They lack requirements for real-time monitoring to identify and protect UCH discoveries during operations. Mining activities could affect Indigenous practices like shark calling. These activities threaten cultural connections to the ocean that span generations.

Regulatory Landscape

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) regulates seabed mining in international waters. The ISA was created in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) with the goal of ensuring that seabed mining is carried out in a sustainable and responsible manner. However, the regulatory framework is still evolving, and many countries are calling for stricter regulations or even a moratorium on seabed mining until more is known about its environmental impacts.

Global Opposition

Opposition to seabed mining is growing, with numerous countries and organisations advocating for a pause in mining activities. Nations like Germany, France, and New Zealand have expressed concerns about the potential risks to marine life and ecosystems. Many scientists are also calling for a halt to seabed mining until comprehensive studies can assess its ecological implications.

Financial Viability and Industry Pushback

The financial world shows growing scepticism about seabed mining’s economic potential, adding to existing environmental and ethical concerns.

Investor Withdrawals and Stock Performance

Financial institutions are quick to step away from the industry. Currently, 64 companies and financial institutions support a moratorium on deep seabed mining. Several major banks, including Lloyds, NatWest, Standard Chartered, ABN Amro, and BBVA, have ruled out financing these projects. Corporate support continues to dwindle. Lockheed Martin sold its seabed resources subsidiary in March 2023, and shipping giant A.P. Moller-Maersk sold its stake in The Metals Company (TMC).

TMC’s story highlights the sector’s financial difficulties. The company’s share price dropped 90% within 12 months of its September 2021 IPO. NASDAQ has sent multiple delisting notices to TMC because its trading price consistently stays below USAUD 1.53.

Cost of Failure: Nautilus Minerals Case Study

Nautilus Minerals’ Solwara 1 project serves as a stark warning. The venture, once celebrated as the world’s first deep-sea mine, collapsed after funding for its production support vessel ran dry during construction. Papua New Guinea’s enthusiasm led to a 30% stake purchase in the project, resulting in a AUD 240.05 million loss of public funds.

Prime Minister James Marape called the venture “a total failure.” In 2019, the company filed for bankruptcy and was liquidated with zero assets, leaving PNG unable to recover its investment.

Corporate Greenwashing and ESG Scrutiny

Mining companies try to portray their activities as environmentally friendly. The Metals Company announced plans to start Pacific Ocean operations in 2025 without formal approval. Other companies present themselves as “research organisations” instead of extraction companies.

Financial analysis contradicts these sustainability claims. A 2023 International Seabed Authority report acknowledged “high uncertainty around prices” for commercial production. This has prompted 37 financial institutions to ask governments to stop seabed mining until they better understand the environmental and economic risks.

The Future of Seabed Mining

As the demand for critical minerals continues to rise, the future of seabed mining remains uncertain. While it presents significant economic opportunities, the environmental risks cannot be overlooked. Seabed mining’s viability will rely on striking a balance between resource extraction and environmental protection.

Alternatives to Seabed Mining

Investigating alternatives to seabed mining is crucial in order to meet the increasing demand for minerals. Recycling existing materials, improving recovery rates, and investing in sustainable mining practices on land could help reduce the pressure on ocean resources. Additionally, advancements in battery technology may lessen the reliance on certain minerals, further diminishing the need for seabed mining.

Conclusion – Seabed Mining

Seabed mining is a complex and multifaceted issue requireing careful consideration of both its economic potential and environmental consequences. As we navigate this uncharted territory, it is vital to prioritise sustainable practices and engage in open dialogue about the future of our oceans. The stakes are high, and the decisions we make will shape the health of our planet for the long run.

In the end, the question remains: can we responsibly harness the riches of the deep sea without sacrificing the very ecosystems that sustain life on Earth? Only time will tell.

Related Articles: De Grey Mining Insights – Who’s Buying & Hemi Project Updates

What are some environmental concerns associated with seabed mining?

The primary environmental risks include the generation of sediment plumes that can harm marine life, long-term habitat disruption with recovery times spanning thousands of years, potential loss of undiscovered species, and disturbance of carbon sequestration processes in deep-sea sediments.

How does seabed mining work?

Seabed mining uses remotely operated vehicles to collect mineral-rich deposits from the ocean floor, typically at depths of 4,000-6,000 metres. These vehicles use suction devices or water jets to dislodge and collect minerals, which are then transported to surface vessels through a riser system for processing.

What are the alternatives to seabed mining for obtaining critical minerals?

Alternatives include developing next-generation batteries that require fewer critical minerals, enhancing metal recycling and urban mining practices, and improving the efficiency of land-based mining operations. These approaches could potentially reduce the need for seabed mining.

Is seabed mining financially viable?

The financial viability of seabed mining is increasingly questioned. Many investors and financial institutions have withdrawn support or pledged not to finance such projects. Past ventures like Nautilus Minerals have failed, resulting in significant financial losses and highlighting the economic risks associated with the industry.